Lives of the Saints

|

Toolbox to Holiness

(first, read the life of the saint above)

|

Learn more about these Saints

|

|

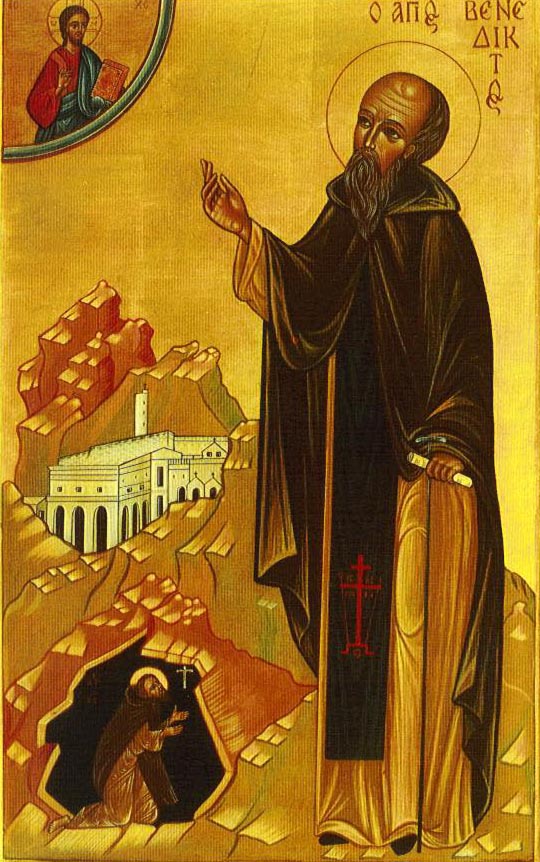

St. Benedict of Nursia

Ora et Labora

(Pray and Work)

St. Benedict of Nursia (ca. 480 – ca. 547) profoundly

impacted the life of the Church in the West. As

the founder of Western monasticism, his Rule has been

the model for most religious orders founded over the

last 1500 years. He is the patron saint of Europe

(declared by Pope Paul VI in 1964, declared co-patron

with Saints Cyril and Methodius by John Paul II in 1980)

as well as the patron of monks, speleologists (the study

of caves), farmworkers and victims of poisoning.

St. Benedict was born at Nursia, a small town near

Spoleto in central Italy. He is known to be the

twin brother to St. Scholastica. Their mother died

at their birth. St. Scholastica and St. Benedict

developed a close relationship early in life that lasted

throughout their lives. St. Benedict was born at Nursia, a small town near

Spoleto in central Italy. He is known to be the

twin brother to St. Scholastica. Their mother died

at their birth. St. Scholastica and St. Benedict

developed a close relationship early in life that lasted

throughout their lives.

His parents were wealthy landowners

(but not part of the aristocracy). St. Benedict

was sent to Rome to study around 500a.d. but decided to

drop out after he was distressed by the immorality of

the Roman culture and the lackadaisical attitude of his

fellow students. He then headed south to the

mountains. There he met a monk named Romanus who

showed him a cave where he could live as a hermit in the

area called Subiaco, which had a spectacular view of the

mountain gorge. Romanus, sensing the specialness

and holiness of St. Benedict, brought food to St.

Benedict every day by lowering it in a basket from the

edge of the cliff. A bell at the end of the rope

would indicate to St. Benedict that his meal had

arrived. He lived like this for about three years.

One day, nearby shepherds stumbled

upon his cave. At first, they were frightened by

the site of St. Benedict (who dressed in animal skins

and looked more like a wild man than a monk). As

they began to speak with St. Benedict, they realized

they had found a saint. So they began a reciprocal

relationship… the shepherds brought him food and he

taught them about the faith.

St. Benedict’s reputation for

sanctity spread throughout the region and men who wanted

to pursue the religious life flocked to him. He

organized them into twelve communities of ten monks each

and an abbot. He stayed there for about

twenty-five years, as roman nobles would send their sons

to St. Benedict to be educated. Among the first

were Saints Maurus and Placid, who came as young boys

and stayed on to become two of St. Benedict’s most

faithful disciples.

During these twenty-five years that

he stayed in Subiaco, he met resistance regarding the

strict regime he required of the communities. The

success of his communities brought about envy and

jealously, at least with one priest named Florentius.

Florentius was known to spread lies about St. Benedict,

though no one believed him. He tried to keep men

from joining St. Benedict, but men kept coming. It

was said that Florentius even tried to poison a loaf of

bread and deliver it to St. Benedict, begging him to

accept it as a token of remorse. By the grace of

God, St. Benedict realized the bread was poisoned.

He was said to have given it to a raven, commanding the

raven to take the bread to a place where no one would

find it. In a final effort to ruin St. Benedict’s

reputation, Florentius hired prostitutes in vain, hoping it

would seduce the monks.

Realizing that Florentius would

never stop his attacks on the community, St. Benedict

moved his monks to Monte Cassino, in the imposing

mountains of the central Apennines in Italy. They built

a new monastery on the summit, converting an old temple

of Apollo into a chapel dedicated to St. Martin.

His sister, St. Scholastica, established a community of

nuns nearby, and they would meet half-way in between

once a year to break bread and discuss spiritual

insights. It was at Mount Cassino where he wrote the

final version of his Rule (of life) (known as the Rule

of St. Benedict). Drawing ideas from monastic

writers such as Saints Basil, John Cassian, Augustine,

the Desert Fathers, Pachomius in Egypt and the Regula

Magistri (“Rule of the Master”), he developed his Rule

to assist the monks to grow in holiness and to live in

community. The Rule of Benedict he wrote for his

monks was in part a reaction against the extremes

practiced by some monks, particular those who lived in

the deserts of the East. Left to their own

devices, these monks, almost all of whom lived as

hermits, would literally torture their bodies by

depriving themselves of sleep, food and water. St.

Benedict’s response was to develop a method that was

practical, made no irrational demands of the body and

could be flexible without compromising its spiritual

principles. It was designed as a different way to

achieve holiness and connection to God. The rule

is divided into 73 short chapters, which focus on three

main themes: Stability, Obedience and Conversion

in Life.

St. Benedict never became a priest,

nor did he intend to form a new religious order.

However, his Rule and his spirituality not only

influenced the growth of Western monasticism, but of

Western civilization itself. He was able to

influence/shape a culture that he once found to be

despicable. He died on March 21 (ca. 547) and is

buried in the Oratory of St. John the Baptist at Cassino

alongside his sister, St. Scholastica. His

monastery in Mount Cassino was destroyed by the Lombards

(ca. 577). St. Benedict’s Rule was followed in

France, England and Germany by the seventh and eighth

centuries. When the emperor Charlemagne (ca.

742-814) initiated a reform of monasticism, he chose the

Rule of St. Benedict as his model. His son and

successor, Louis the Pious imposed it on all monasteries

within the empire. His motto is “Ora et Labora”

which means “Pray and Work.” We celebrate his

feast day on July 11.

Resources on St. Benedict

|